Community conversations center segregation and reparations in Essex County suburbs

Attendees at events in Maplewood and Montclair discussed the impact of redlining, systemic discrimination, and reparations at forums hosted by The Jersey Bee.

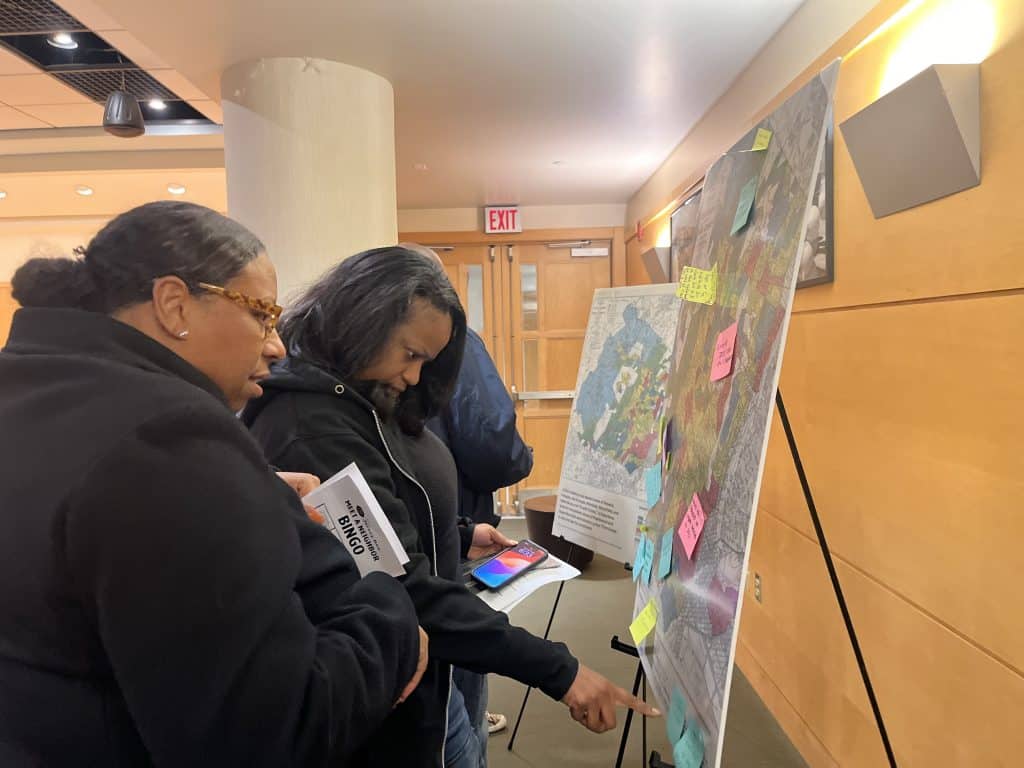

The Jersey Bee hosted two community forums on segregation and reparations Oct. 8 and 17 at The Woodland in Maplewood and Montclair Public Library in Montclair, New Jersey.

Both events included an introduction to segregation in New Jersey and community mapping activity led by Simon Galperin, executive editor at The Jersey Bee, followed by a community panel moderated by Kimberly Izar, public health reporter at The Jersey Bee and segregation reporting fellow at Next City.

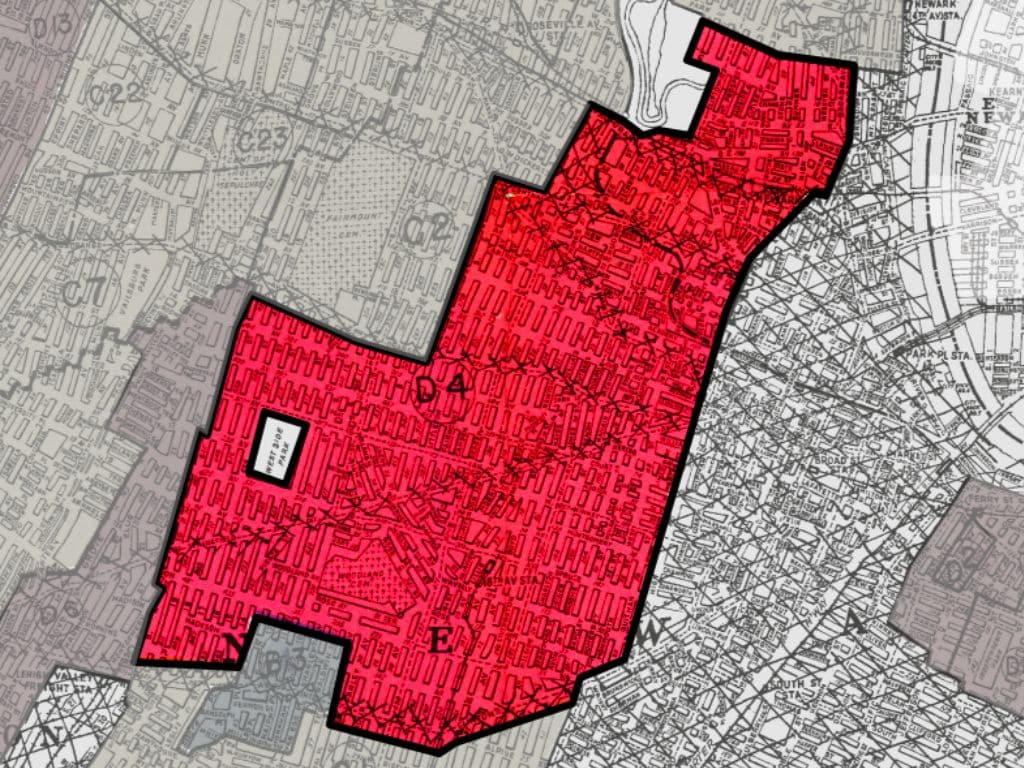

Attendees gathered around maps created in 1930s by the federal government that “redlined” Black communities. The maps highlighted different neighborhoods across Essex County, along with the descriptions the federal Home Owners’ Loan Corporation wrote to describe their value.

South Orange Central

Central South Orange was described as “an area of the lowest type although not a slum. Centrally located near the R.R., business and some industry, it has no appeal as a residential neighborhood except at lowest price levels.” A number of homes were “being used as negro rooming houses. Most flats are unheated.”

Image from Mapping Inequality: Redlining in New Deal America.

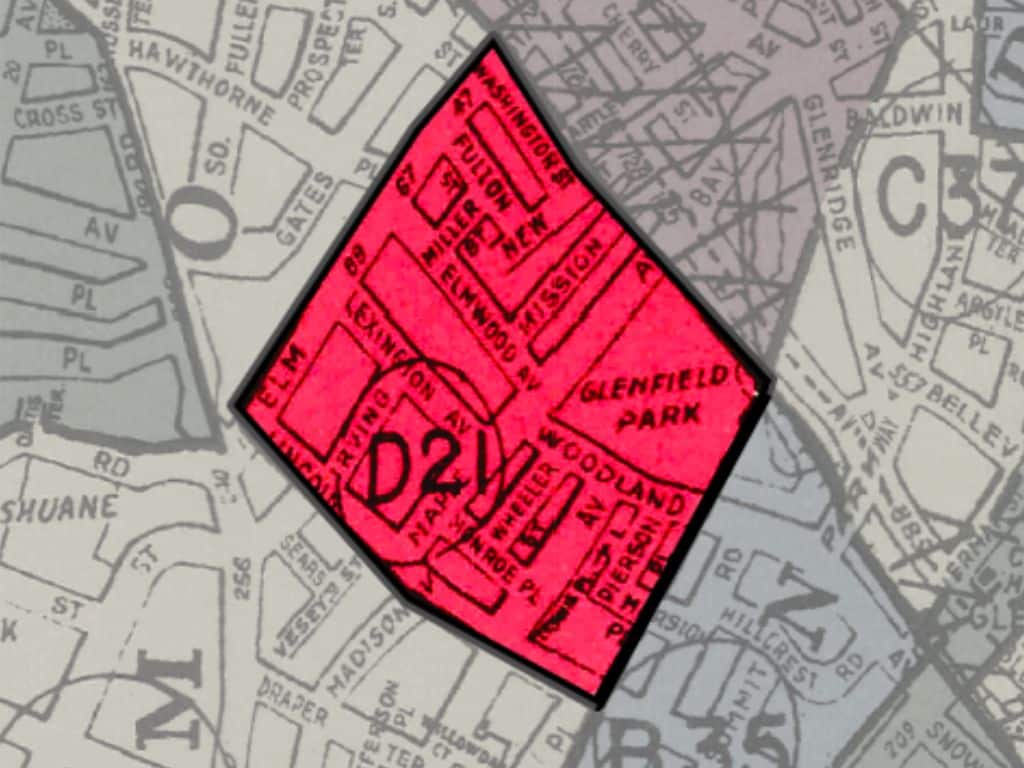

Maplewood, East of Valley Street

East of Valley Street in Maplewood was described as having “good transportation of all kinds, schools, etc.” However, the federal government added that this “first class area” also had “one very small section south of Millburn Avenue which contains a mixture of Negroes and Italians. This is not spreading. “

Image from Mapping Inequality: Redlining in New Deal America.

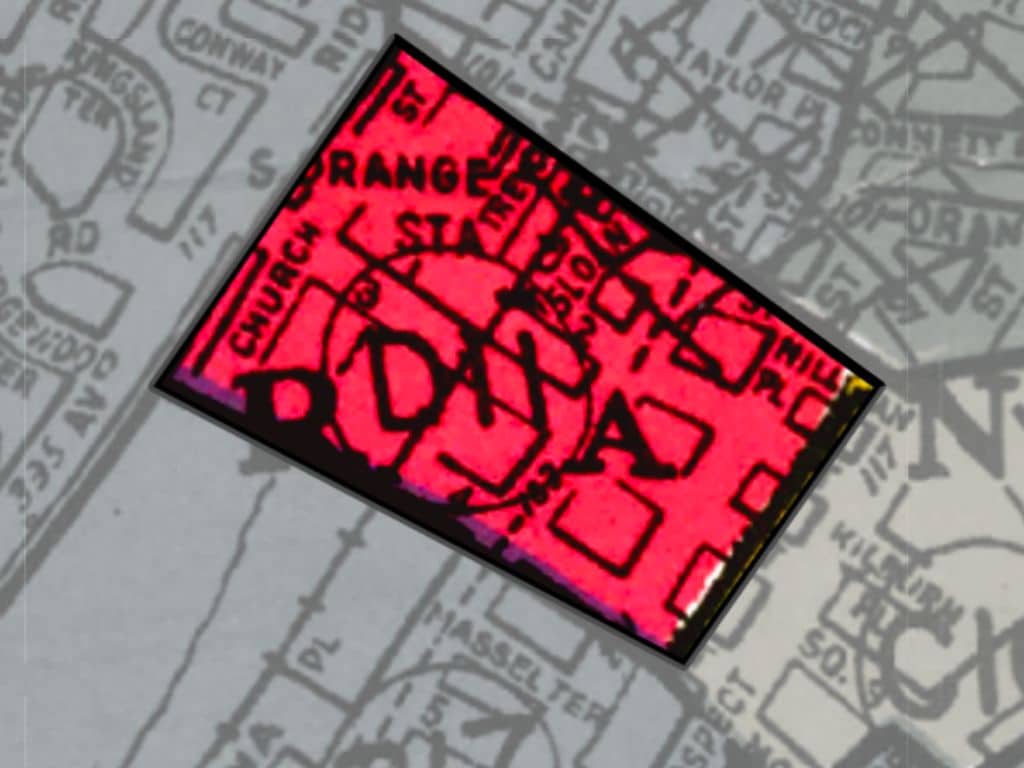

Newark’s Central Ward

Newark’s Central Ward, then known as the Third Ward, was described as “Newark’s worst slum section” with “considerable demolition and boarding-up” and “useful only to those in lowest income brackets who need to be in walking distance of work.”

Image from Mapping Inequality: Redlining in New Deal America.

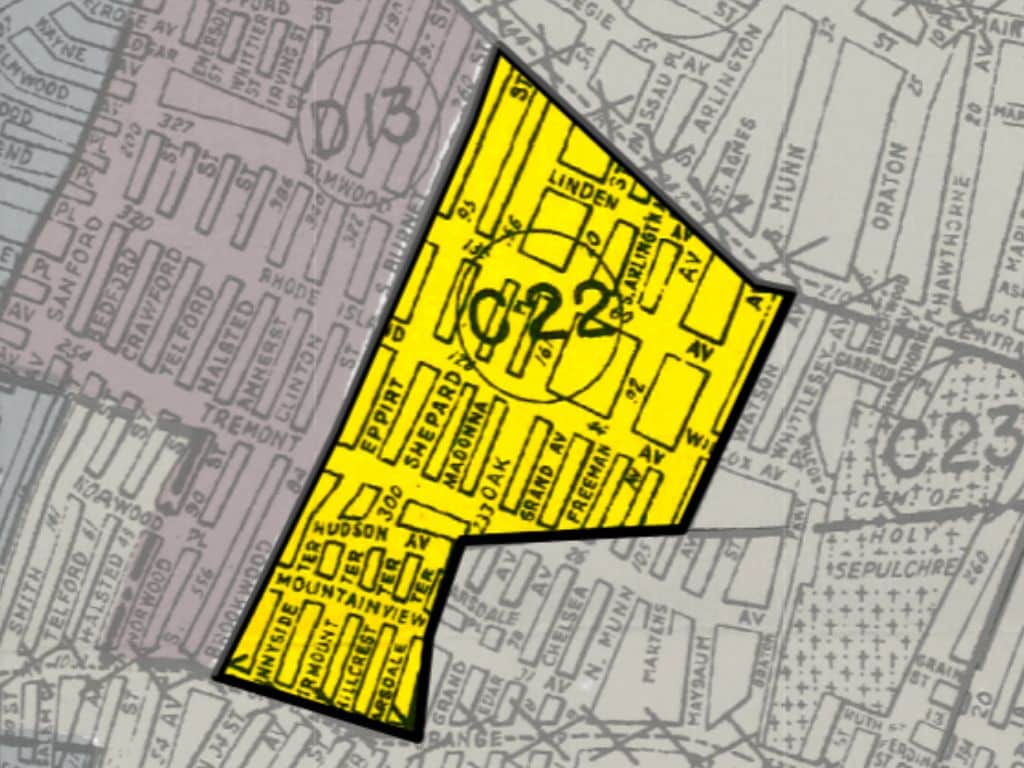

Montclair’s South Side, South of Bloomfield Ave

This neighborhood in Montclair’s South Side was described as “100% improved. All city facilities, convenient to everything. Excellent transportation of all kinds. This district houses the greater part of Montclair’s large negro population. Most of these are employed locally as domestics, gardeners, chauffeurs, etc.” Yet still “a proposal for slum clearance [had] recently been defeated on the basis of lack of necessity.”

Image from Mapping Inequality: Redlining in New Deal America.

Montclair’s South Side, East of Eagle Rock Reservation

A Montclair South Side neighborhood east of Eagle Rock Reservation was described as “contain[ing] a few houses that have been occupied by negroes for many years, but there is no apparent possibility of spreading.”

Image from Mapping Inequality: Redlining in New Deal America.

East of Grove Street in East Orange

East of Grove Street in East Orange was described as slowly deteriorating due to “infiltration of poorer inhabitants and the threat of increased negro families.”

Image from Mapping Inequality: Redlining in New Deal America.

Galperin asked attendees to share their observations, personal stories, and questions with one another. Attendees discussed and added post-it notes to a map and shared observations on specific areas:

- “Limited tree cover in [South] Bloomfield.”

- “Would be targeted for urban renewal.”

- “The green [part] of Montclair [is] still primarily white.”

- “Springfield Ave. dividing line.”

- “Desirable section of Irvington near Maplewood [once] called ‘Upper Irvington.'”

- “Glen Ridge [houses] had covenants prohibiting their sale to Black or Jewish people.”

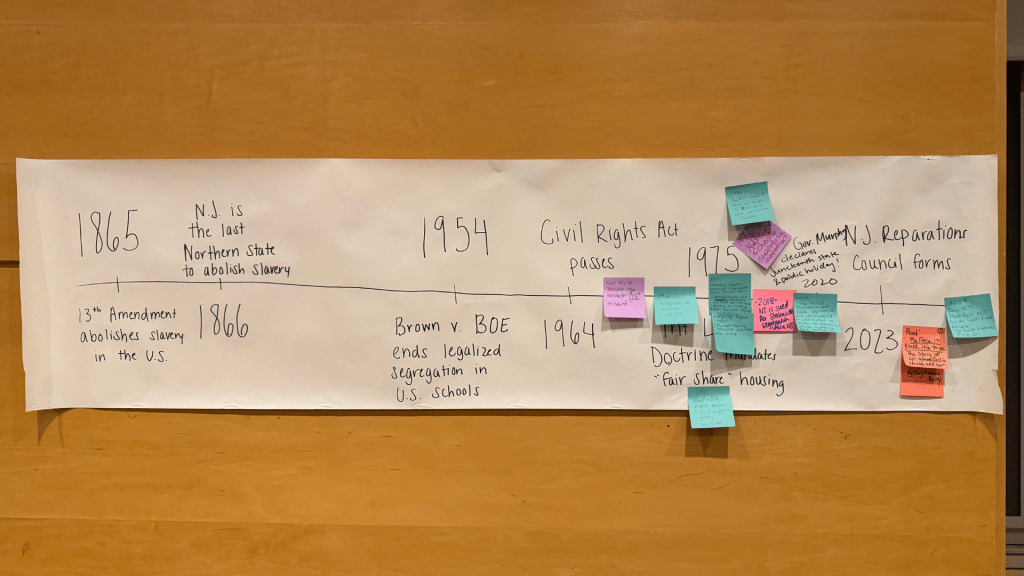

“Even as slavery began to be incrementally taken apart in New Jersey – because of our economic ties, the state was inextricably tied to the economy of the south and benefited immensely from enslaved people,” said Galperin during his opening remarks.

Sometimes referred to as the “slave state of the North,” New Jersey was home to more than two-thirds of all enslaved Black people in the Northern United States by the 1830s. Slavery was abolished in New Jersey in 1866 following the Civil War, but its impact on Black communities still impacts the state’s current economic, education, and housing systems.

“Despite ongoing racial prejudice following the war, Black Americans became the cornerstone of thriving multicultural communities throughout the country and the state,” Galperin said. “[By the 1920s,] studying what happened in the South, we see countless lynchings and [racist violence].”

“At the time in New Jersey, Princeton [University] banned the admission of Black people to the school. Local governments passed laws segregating beaches, recreation centers, and schools. The Ku Klux Klan marched and met in Bloomfield, Newark, Trenton, and other cities. They burned crosses on lawns throughout North Jersey, including [in] Montclair. In Washington, D.C., the federal government starts segregating its departments and limiting Black people to certain roles.”

“And it’s in this environment that the federal government decides to increase residential development,” Galperin continued. “And they draw these maps that are on our tables…that they say that Black communities, multicultural communities, aren’t a good investment. And this limits the people that live there from accessing economic and social resources like banking and healthcare. It subsidizes development in majority white communities, suburban communities, and today when we look at racial and class disparities in wealth, education, healthcare, and housing, much of it is tied to decisions made about who is worthy of economic investment 100 years ago.”

READ: In Essex County, New Jersey’s history of segregation persists

Following the community mapping activity, speakers including community leaders, local history experts, and racial justice advocates shared local perspectives. In Maplewood, the panelists were Khadijah White of SOMA Justice and Nancy Gagnier and Audrey Rowe of the SOMA Community Coalition on Race. In Montclair, Angelica Diggs from Montclair History Center, Nicole Gray from Friends of the Howe House, and Jacob Faber, a New York University professor and New Jersey Reparations Council member, headlined the conversation.

Why we hosted the forums

In June, The Jersey Bee partnered with Next City, a nonprofit news organization amplifying solutions to the problems that oppress people in cities, to understand what it takes to reimagine Essex County and New Jersey as equitable and just places.

As a public news service producing reporting that meets local information needs, The Jersey Bee prioritizes responding to information and accountability gaps that disproportionately impact communities of color, the working class, and other historically marginalized people.

After several months of listening and reporting, we decided to host forums to connect people with each other while learning about segregation and movements for reparation in their neighborhoods.

In doing so, The Jersey Bee aimed for the event to be reparative: produced in collaboration with local organizers and intentionally held in New Jersey suburbs, where residents benefit from a legacy of redlining and segregation.

“Conversations like this help us say to our children…‘No, you didn’t do anything wrong. Here is your history. It’s part of the whole,” said Nicole Gray, board member of Friends of the Howe House.

What we heard

Current power structures enable some residents who benefit from segregation to maintain inequitable practices

Audrey Rowe, Program Director of SOMA Community Coalition on Race, said that her organization often gets asked what segregation should mean to them if they are not a person of color. “We all have a stake in it,” Rowe said.

Redlining left Black communities vulnerable to predatory lending and reliant on renting instead of homeownership. In Essex County, more than two-thirds of white families own their homes compared to just 28 percent of Black families and 34 percent of Latinx families, according to a New Jersey Institute for Social Justice report.

Nancy Gagnier, Executive Director of SOMA Community Coalition on Race, added that there is still a “zero-sum game attitude” – even for people who moved to South Orange-Maplewood “for the diversity.”

“Part of our work [is] to help people overcome that mindset, that integration, equitable practices serve everyone,” said Gagnier.

Essex County continues to struggle with a defacto culture of segregation, according to several panelists.

Khadijah White described her experience as a Black student being dropped two academic levels while enrolling in the predominantly-white South Orange school system despite being considered a high-performing student at her previous school. “That was what it was like to be a black kid here…You were fodder for the white kids, actually, so that they could build on top of you, especially when the levels all boosted your GPA, right?”

White was soon moved into a higher-level class after a teacher recommended her, a practice she highlighted as a source of inequity.

“So you couldn’t actually catch up, even if you were straight-A student in level three…to the kids who were put by teacher recommendation in the level five class.”

As an adult, White is among the panelists who see a culture of segregation persisting in Essex County. White encouraged attendees to challenge “this belief that people don’t know what’s happening and throw that away,” adding there are white people who like and benefit from the racial “hierarchy.”

Reparations can take many forms

During both events, panelists discussed how repair can take many forms – from wealth distribution to thinking about historical sites as places of repair.

The Howe House is one blueprint for what a place of repair could be, said Nicole Gray, board member of Friends of the Howe House. The house is the historic home of James Howe, a formerly enslaved Black man freed in 1817 in Montclair, that now serves as a home for education and reflection of the past, present, and future for Black Americans.

“We have to use the Friends of the Howe House as a point of reference for preserving our history, but also using it to say [New Jersey] had slavery. Now, we need to address it,” said Gray.

Jacob Faber, a member of the New Jersey Reparations Council, said it’s critical to consider the institutional framework in which racial inequities exist when thinking about repair.

“Segregation [is] not just a geographic story. It’s a power relationship, and this relationship is constructed and reconstructed by everyday actions of all of us in this room, intentionally or not, to siphon resources from some neighborhoods… and pull them into others,” said Faber.

Convened by the New Jersey Institute for Social Justice, a nonprofit advocacy organization, the New Jersey Reparations Council came together on Juneteenth 2023 to launch a two-year study on the harms of slavery and racial segregation and propose recommendations for reparations. The final report is expected to be released on Juneteenth 2025.

Faber added that while there has to be a transfer of wealth, “that’s only a starting point. It also requires realignment across the board.”

READ: Advocates will propose a reparations plan for New Jersey. Here is what residents should know

What’s next

Over the last few months, The Jersey Bee and Next City have explored solutions to address segregation in Essex County, including land use, reproductive health care, food insecurity, and more. We intentionally brought what we learned into the community through in-person events, one-on-one conversations with residents and policymakers, and partnerships with other newsrooms to expand our reach.

We also heard that diverse groups of residents were ready to engage in thoughtful dialogue about major issues if the conversations were community-informed and solutions-oriented.

“The Jersey Bee thinks about how we culturally integrate this traditionally redlined community,” executive editor Simon Galperin told attendees in Montclair. “The way we serve the community, the way we report news, we think about not replicating media redlining like [traditional media.]”

Learn more

Explore digital versions of the redlining maps featured during the events in Mapping Inequality: Redlining in New Deal America.

Learn more about the organizations featured in the event and other collaborators:

- SOMA Justice

- SOMA Community Coalition on Race

- SOMA Action

- New Jersey Reparations Council

- Montclair History Center

- Friends of the Howe House

- Montclair Public Library

What makes The Jersey Bee different? You.

When The Jersey Bee decides to report something it's because you told us about it.

We take the “public service” in public service journalism seriously. So our reporting responds to your needs and asks the questions that matter to you.

The Jersey Bee does journalism differently because we listen to our community so we can report news that meets local needs and increases civic participation.

The Jersey Bee works with the people we serve to improve the quality of life in our community. Together, we’re building a more accessible and connected community for all.