In Essex County, New Jersey’s history of segregation persists

The Jersey Bee is launching a project with Next City to explore segregation in Essex County and New Jersey. Here is what we know about the former “slave state of the North” and what you can do to help us report.

Share your experience with segregation in Essex County at the survey below this article or find it here.

Minutes from one of the busiest train stations in the state is the former home of Lieutenant Colonel Thomas Cadmus in Bloomfield, N.J. Cadmus is remembered locally as a respected Revolutionary War officer and founder of the town’s historic Presbyterian Church on the Green, but a lesser-known truth is that he also enslaved people.

Behind Cadmus’s house in Bloomfield was a kitchen and his slave quarters, where he enslaved some of New Jersey’s approximately 4,700 enslaved Black people in the mid-1700s.

Spend some time driving through Bloomfield, Newark, Montclair, and other municipalities in Essex County, and it isn’t hard to find remnants of the state’s violent legacy of slavery – in street names, in library archives, or engraved on historical landmarks. Cadmus was far from the only enslaver in the area. Neighboring Bergen County was the epicenter of the state’s enslavers because of its access to ports and mines, where they enslaved Black people as free labor.

New Jersey was referred to as the “slave state of the North” and home to more than two-thirds of all of the enslaved people in the Northern United States by the 1830s.

While slavery was abolished in the United States in 1865, the legacy of slavery and unequal treatment continues in New Jersey’s housing, education, healthcare, and other systems today.

Over decades, the system of chattel slavery, where people were treated like property and forced to work, has evolved into modern-day segregation, a systematic practice that disenfranchises Black and other historically exploited groups in nearly every aspect of daily life.

According to the New Jersey Institute for Social Justice, Black and Latinx households in Essex County are half as likely to own a home than white households and three times more likely to live in poverty than white residents. New Jersey’s Black and Latinx residents are also more likely to be uninsured than white residents, which has been shown to lead to greater health risks and poorer quality of care, according to the New Jersey Department of Health.

“We think of New Jersey as kind of a microcosm of Dr. [Martin Luther] King Jr.’s concept of two Americas, and in fact, I think that Essex County is almost a microcosm of that even more so,” said Laura Sullivan, Economic Justice Director of the New Jersey Institute for Social Justice.

In 2023, The Jersey Bee sought community insights on how segregation manifests in housing and schooling in New Jersey through Segregated, a statewide collaboration of news organizations reporting on the topic. We heard from more than 30 Essex County community members who shared concerns about the lack of investment in majority-renter neighborhoods, segregation in elementary schools, procedural injustices in education, and a culture of racial discrimination when looking for a home or school.

Guided by community feedback and ongoing conversations we’ve had with others on the topic of segregation and reparations, we recognized that a deeper understanding of racial and systemic inequities was needed to support residents in implementing solutions to the challenges they face on these issues.

That’s why The Jersey Bee partnered with Next City, a nonprofit news organization amplifying solutions to the problems that oppress people in cities, to understand what it takes to reimagine Essex County and New Jersey as equitable and just places.

Through 2024, The Jersey Bee will collaborate with Next City and deepen our coverage to explore how racial and economic segregation manifests today and how the region can address it.

Here’s what you can expect going forward.

What do we know about segregation in Essex County?

Housing

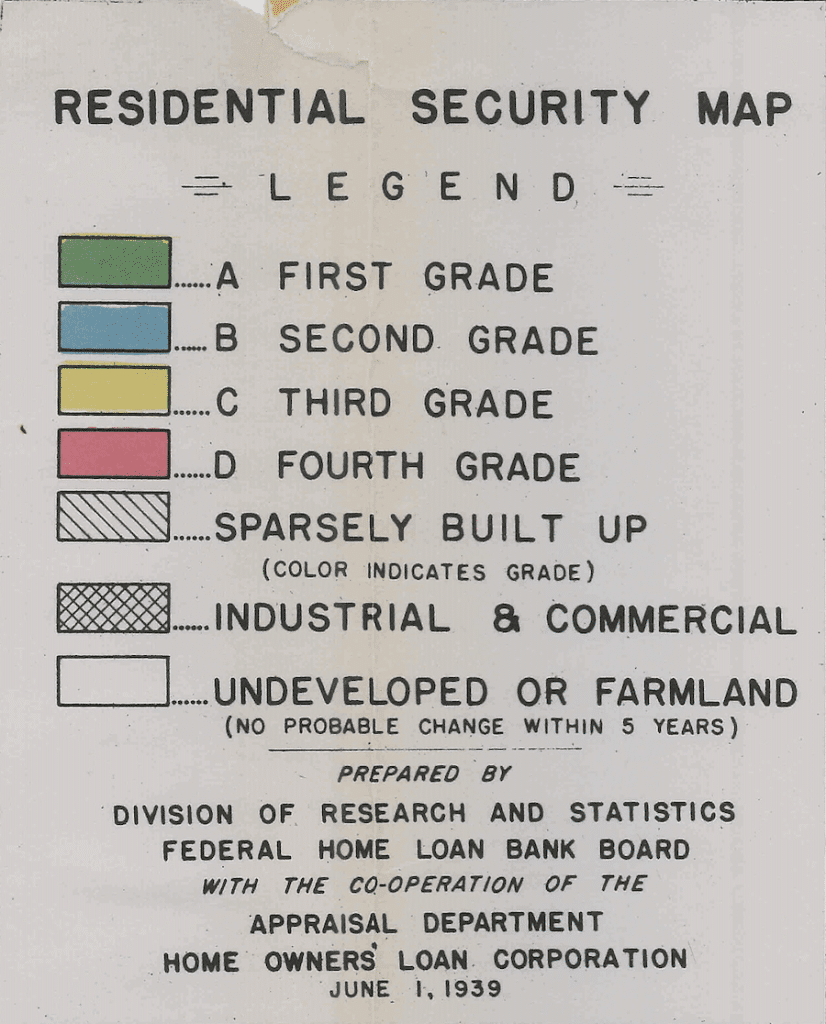

In the 1930s, the federal government’s exclusionary process known as ‘redlining’ drew red lines around Black neighborhoods and deemed these areas investment risks, essentially locking Black families out of fair mortgages, bank services, and other wealth-building opportunities.

The federal government used racialized and dehumanizing language to red-zone and describe areas across Essex County where Black residents lived.

- Newark’s Ironbound neighborhood was described as “Newark’s worst slum section” with “considerable demolition and boarding-up” and “useful only to those in lowest income brackets who need to be in walking distance of work.”

- Montclair’s South Side neighborhood was described as “contain[ing] a few houses that have been occupied by negroes for many years, but there is no apparent possibility of spreading.”

- East of Grove Street in East Orange was described as slowly deteriorating due to “infiltration of poorer inhabitants and the threat of increased negro families.”

The impact of redlining left Black communities in Essex County at risk of further predatory lending practices, appraisal bias, and a reliance on renting instead of homeownership. Some residents are concerned that a culture of segregation remains deeply entrenched.

Residents aren’t the only ones noticing ongoing racial discrimination in housing in Essex County. In 2022, the federal government fined New Jersey’s Lakeland Bank in $13 million to settle a lawsuit alleging it avoided opening branches in Black and Latino communities and giving mortgages to people of color.

Education

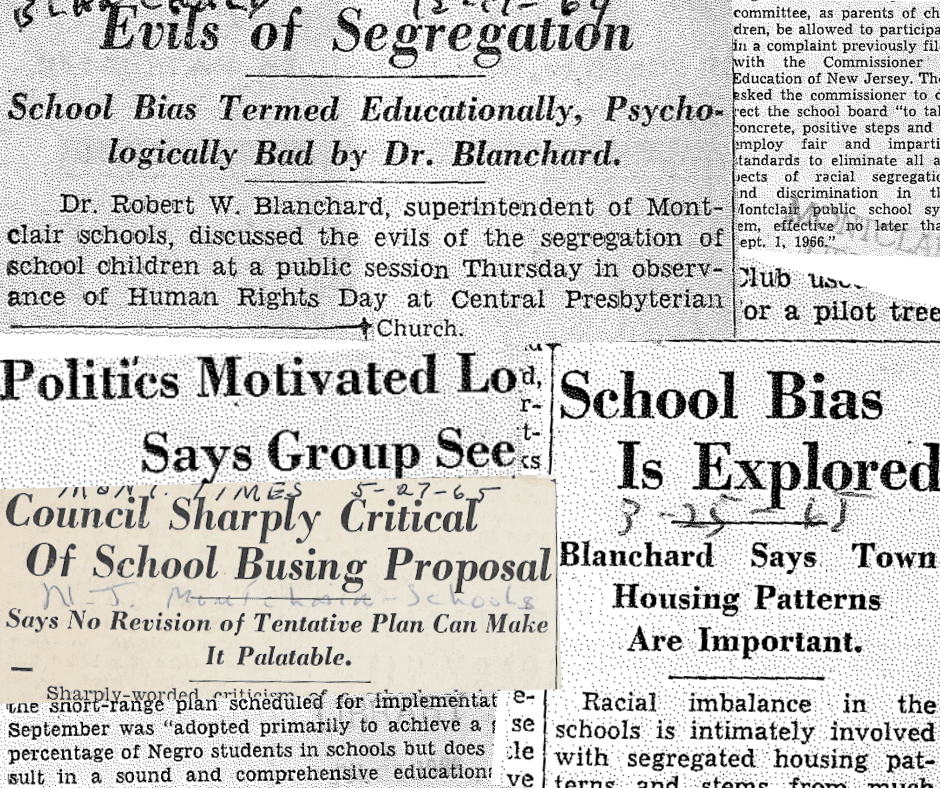

Segregation is also deeply embedded in Essex County’s schools. In particular, the Newark area has some of the country’s most segregated schools and is central to a six-year lawsuit the state faces about school integration.

In 2018, a group of students, families, and advocates sued New Jersey, alleging that school segregation deprived students of their rights to a quality education. Negotiations are still underway after New Jersey’s Supreme Court found that the state’s schools are “indeed segregated but that this did not amount to a ‘statewide’ constitutional violation.”

This isn’t the first time the New Jersey Supreme Court weighed in on segregation in the state. In 1975, the court ruled that the state’s municipalities had to provide their “fair share” of affordable housing through the Mount Laurel Doctrine.

In the following decades, some New Jersey communities diversified their school systems, but loopholes and weak enforcement left many schools disproportionately white.

Healthcare and other systems

Today, segregation is enforced and underdetected in areas beyond homeownership and schooling, like access to quality healthcare and disaster relief.

A 2024 report from The Commonwealth Fund shows that New Jersey’s Black and Latinx residents die from preventable causes at significantly higher rates than white and Asian residents.

In 2015, low-income and communities of color in Newark faced disproportionate neglect from federal assistance programs following Hurricane Sandy, according to a Fair Share Housing Center report. The report highlighted that Black and Latinx residents were more likely to be exposed to mold, toxins, and other environmental hazards than white residents after the storm. Some of these impacted areas continue to face environmental harm due to their proximity to hazardous waste facilities, air pollution, and sanitary landfills, according to mapping from the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection.

What’s being done to address segregation in New Jersey?

In December 2023, the New Jersey Senate narrowly passed a bill that would fine property appraisers who discriminate “on basis of race, creed, color, national origin, or certain other characteristics.” The bill was referred to the Assembly Housing Committee but never made it to a floor vote.

Policymakers have also tried to introduce legislation and resurrect past bills to explore the impact of slavery and make recommendations towards repair as far back as 2005. However, reparation-related bills stalled and also never reached the floor for a full vote.

In response, the New Jersey Institute of Social Justice launched the New Jersey Reparations Council in 2023 to research and recommend ways to accomplish reparation in New Jersey.

The New Jersey Reparations Council’s David Troutt says that segregation continues to devastate the state’s residents.

“New Jersey is one of those states that is fundamentally organized around the principle of segregation,” said David Troutt, a member of the New Jersey Reparations Council, during the council’s one-year update on Juneteenth 2024 in Newark, N.J.

Troutt said that segregation policies cleverly underwrite the state’s racial wealth gap, education, and public health outcomes. “It’s important to understand how these things rig the market and establish the rules even if they’re unwritten by which people continue to conduct business.”

What’s next?

Over the next few months, The Jersey Bee will collaborate with Next City to explore how segregation impacts residents in Essex County and what solutions bring us closer to a more just and equitable future.

We’ll explore this issue from our understanding that segregation is systemic. To us, segregation is the act of excluding a group of people based on race, gender identity, sexuality, disability, economic class, or immigration status through practice or policy, including forms of policing, urban design and zoning, and other practices that enforce systems of division and oppression.

We’re paying close attention to the issues residents have said mattered to them, including housing, transit, education, policing, food access, climate resilience, and healthcare. We want to know how segregation affects people’s ability to own a home, access quality education, grow food, move freely, feel safe in their neighborhoods, and work with dignity.

We’re especially interested in hearing how these issues affect BIPOC, undocumented, LGBTQIA+, veterans, people with disabilities, immigrants, non-English speakers, and residents in areas that are more likely to be harmed by segregation, such as low-income and majority-renter communities.

How to get in touch

If you’d like to share your thoughts, tips, or personal experiences with segregation in Essex County, we’d love to hear from you. You can reach out to Kimberly Izar at kimberly@jerseybee.org or complete the survey below.

We’re also looking for partners who can help us deepen our reporting and foster meaningful dialogue with community members! If you’d like to explore ways to collaborate, please reach out to Kimberly.

Learn more

Read reporting from Segregated, a collaboration between NJ Spotlight News, WNYC, The Village Green, Central Desi, and other news organization that examined segregation in a 2023 collaboration.

New Jersey Institute for Social Justice’s decades-long research on segregation in New Jersey can be found here.

Public libraries including Montclair Public Library and Newark Public Library have archived materials related to slavery and segregation. You can check other local libraries in Essex County to see what else is available.